How the AAA® Turned Two Rivals into a Powerhouse of Fairness

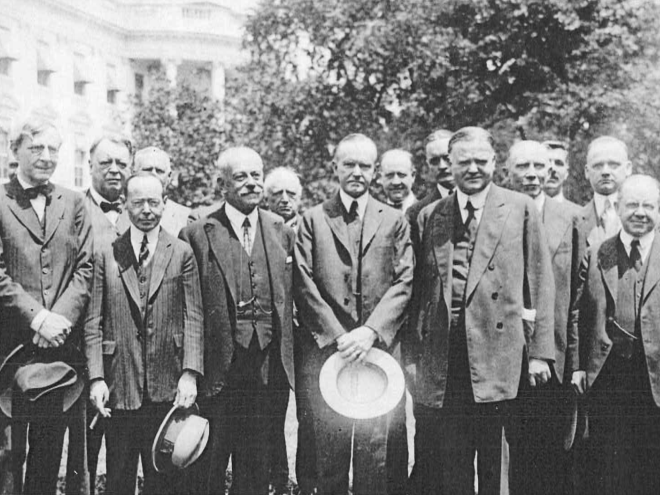

“Arbitration Ends Trade Disputes: New Organization with Commercial ‘Umpires,’ Stops Litigation,” read the headline in the Nov. 6, 1926, Saturday edition of The Tablet.[3] Just 10 months after its founding, the American Arbitration Association® was already making waves.[4]

Top universities, including Harvard, Yale, Cornell, and Brown, had embraced the study and teaching of commercial arbitration.[5] The AAA had the backing of the U.S. Department of Commerce and 243 affiliates, including boards of trade and chambers of commerce. Of the 119 cases it had arbitrated, the average cost was just $20.50, roughly 0.5% of the total claims and counterclaims.[6] The movement for commercial arbitration was gaining ground, and the AAA was proving its worth — but more importantly, a new route to industrial peace was emerging.

It was a remarkable outcome, especially given that the AAA itself had been born from seemingly irreconcilable conflict.

Different Visions

On Jan. 29, 1926, the AAA was created from the merger of two very different institutions: the bold, experimental Arbitration Society of America and the more traditional Arbitration Foundation sponsored by the Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York.[7] Progressive educators, lawyers, small businesses, and average citizens were in one corner and conservative business leaders were in another. The merger bridged the divide, reshaping the future of dispute resolution for a century to come. And the institutions did it by appointing a panel and resolving their differences.[8]

Founded in 1922 by Moses H. Grossman, a former municipal court judge who had witnessed the burdens litigation placed on disputants, the Arbitration Society of America embraced a democratic approach, making arbitration accessible beyond elite circles.[9] Its focus was on popularizing the practice, rooted in the belief that arbitration “must be set free to serve mankind” — that it should be “taken to the doorsteps and housetops of the common people.”[10]

By contrast, the Arbitration Foundation, launched in 1925 and led by Manhattan cotton merchant Charles L. Bernheimer, emphasized precision and rigor, standardizing arbitration through best practices, research, and closer ties with the established business and legal communities. Its goal was to one day export the American concept of arbitration, with its message of cooperation and goodwill, to the world — a sentiment captured in Bernheimer’s 1915 book: “A Business Man’s Plan for Settling the War in Europe.”[11]

In combining the two organizations, the AAA gained the best of both worlds: the Society’s bold, public‑facing energy and the Foundation’s discipline and institutional rigor.

Good Conflict

As Frances Kellor later observed, this tension had a purpose. It forced both groups to rethink arbitration and its role in American commerce, bringing together diverse minds to envision its future. In 1925, each organization appointed a three-person committee to coordinate their efforts and align interests.[12] The result was a bold recommendation: Unite as a new organization that embodied both visions.[13]

That new entity became the AAA — a trailblazer in providing a neutral, credible system of arbitration serving commerce and society. A century later, it still reflects this dual heritage: the Society’s amplification of arbitration and the Foundation’s pursuit of perfecting its practice. At its founding, the AAA embodied arbitration’s original promise — to bring tranquility, fairness, and integrity out of the chaos of conflict — and it upholds that promise to this day, no matter where the next dispute emerges.

For 100 years, the AAA has shaped the future of ADR — fast, fair, and fearless. We break barriers with innovation that expands access to justice for all. Always neutral, never passive, we are the world’s leading alternative dispute resolution service provider. And we’re just getting started.

[1] AAA Archives

[2] 50th pub.pdf, PDF page 4

[3] American Arbitration: Its History, Functions and Achievements, page 18

[4] American Arbitration: Its History, Functions and Achievements, page 17

[5] https://www.newspapers.com/image/836562054/?match=1&terms=American%20Arbitration%20Association

[6] https://www.newspapers.com/image/576349999/?match=1&terms=American%20Arbitration%20Association

[7] American Arbitration: Its History, Functions and Achievements, page 17

[8] American Arbitration: Its History, Functions and Achievements, pages 16–17

[9] Journal of Constitutional Law, page 2,362; American Arbitration: Its History, Functions and Achievements, page 11; Swift Justice Dealt by New Tribunal, The New York Times May 25, 1922

[10] American Arbitration: Its History, Functions and Achievements, page 16

[11] American Arbitration: Its History, Functions and Achievements, pages 15–16; “Science: Merchant Archeologist” Time, August 12, 1929

[12] American Arbitration: Its History, Functions and Achievements, pages 16–17

[13] American Arbitration: Its History, Functions and Achievements, pages 16–17